Last year, projects on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) themed seem to have taken place more than any year since the Sexual Crimes Act was passed in July 1967. Work continues in many organizations, including the British Museum, to ensure that these temporary projects leave a lasting legacy.

according to an article to arkeofili.com, The works in this article were exhibited in the British Museum’s 2017 project “Passion, love, identity: exploring LGBTI history”. In the article, however, some important objects in the museum collection were highlighted, describing what the British novelist E M Forster called “the great unrecorded history”

1- Vase depicting Sappho

Evidence of true female sexuality is difficult to find in ancient Greek and Roman objects, as they often reflect male perspectives. In ancient Greece, women were generally excluded from public life and politics, but they participated in indigenous and religious rituals. The poet Sappho (630-570 BC), who lived on the island of Lesbos, gave voice to women and female desire. Sappho was probably depicted in the figure sitting on this water bowl. In the 19th century, Sappho’s poems created a term for the inhabitants of Lesbos (Lesbos), a term for women who love women. Little is known for certain about Sappho’s life, but his poems have inspired many women who lived in later times.

2- a Mayan ruler

This image of a male Maya ruler was once considered female as she wore a net-shaped jade skirt worn by elite Mayan women. In fact, he is dressed like a young corn god whose gender can be both male and female. Confusion or misunderstanding can occur when gender is read across cultures. There are many instances where early European explorers, researchers, and collectors initially failed or perhaps unwilling to understand values that were different on their own.

3- Warren Cup

Decorated with scenes of two male lovers, this Roman wine mug could not be displayed publicly for much of the 20th century. Homosexuality was illegal in England and Wales until June 1967. But explicit sexual images were not unusual in the Roman world. Relationships between men were part of Greek and Roman culture, from slaves to emperors. The most famous of these was the relationship between Emperor Hadrian and his lover Antinous. Today, such ancient images remind us that societies’ views on sexuality can be very different. The Warren Cup was bought by the British Museum in 1999 and has been on display ever since, except for short periods when it was on loan to other institutions.

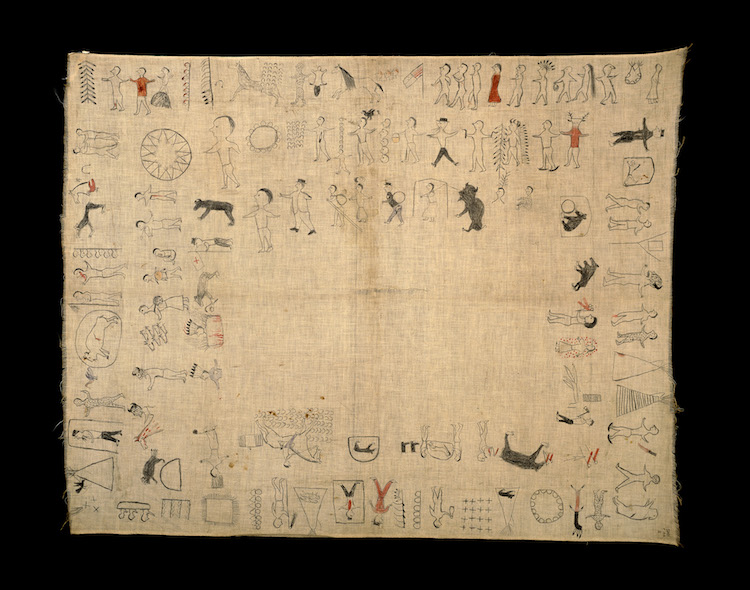

4- Native American records

The “Indian records” were kept as historical records by tribes that lived in some of the North American plains. This is one of many surviving versions of a Sioux record showing events for the winters of 1785-6- 1901-02. The year 1891 includes an image representing the suicide of a winkte. Winkte literally means a Dakota word for wanting to be a woman. Among some Native American tribes, such individuals were considered to have special spiritual powers because they bridged gender differences. Among Dakota Sioux there were about ten registered individuals of this class of people of the same tribe who lived at any time. The arrival of Anglo-Americans led to the suppression of the wearing of opposite sex by these individuals. Today, this tradition has been revived among the younger generations of LGBTI Native Americans.

5- N’domo mask from Mali

In many African cultures, gender and gender-based roles are fixed through rituals. N’domo masks were used by the Bamana people of Mali. They were worn by men, but the masks could be male, female or androgynous. The number of horns on the masks was important: male masks had 3 or 6 horns, female masks had 4 or 8 horns, and bisexual masks had 2, 5 or 7 horns.

Gender and sexual diversity were often suppressed by colonial rulers in Africa, and this was sometimes forgotten, creating the impression that it never existed. Partly as a result of this colonial history and the introduction of Christianity, “homosexuality” has been made illegal in many African countries. Anti-racist and civil rights movements are generally parallel to LGBTI people around the world.

In 2012 Archbishop Tutu said: “I have no doubt that in the future, laws that criminalize many love and human devotion will look at how discrimination laws are treating us now – it will be clearly wrong.”

6- Llangollen Women

Lady Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby fled Ireland in 1778. They set up houses in North Wales, defied the rules of the time and lived the life they preferred for 50 years. Eleanor’s diary gives us an insight into their lifestyle. He wrote on Thursday, September 22, 1785:

“I got up at seven. Dark morning, all the mountains are covered in fog. Heavy rain. There is a fire in the library. I am comfortable with pleasure. I had breakfast at half past eight. I wrote from 9 o’clock to 1 o’clock. My darling is drawing Pembroke Castle. I read him a book from 1 am to 3 pm. After dinner, I hurried around the gardens. It rained all day without stopping. I read it to Sally from 4 to 10. She was drawing, she. We talked with my lover sitting by the fire from 10 am to 11 pm. It’s a quiet and happy day. ”

This pair of chocolate cups belonged to Eleanor and Sarah. These women gained celebrity-like status, and the museum also has several prints depicting them in its collection.

7- Ganymedes statue

In Greek mythology, the god Zeus had a great desire for the beautiful young Ganymedes. He then took the form of an eagle to kidnap Ganymedes, the sakus of the gods. Today, there are many works depicting Ganymedes. The work in the photo is from the Ancient Roman period. Ancient Greece had a great impact on Ancient Rome, including the acceptance of sexual relations between men within certain limits. However, the adoption of Christianity made a significant change in such attitudes. During the medieval period, the term Ganymedes began to mean abuse. The Renaissance led to a renewed interest in classical mythology, including subjects that offered a legitimate way to portray sexual stories. Sculptures like this one were popular with wealthy European collectors in the 1700s and 1800s.

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender & Intersex News Lesbian News, Gay News, Bisexual News, Transgender News, Intersex News, LGBTI News

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender & Intersex News Lesbian News, Gay News, Bisexual News, Transgender News, Intersex News, LGBTI News